Being as large and complex as it is, it was hard to figure out a way to present the Maplewood project clearly and coherently. After some thinking, it seems the best combination of clarity and detail will be to split it into three sections. This section, Part I, will be an overview of the site history and project planning. Part II will examine and break down the site plan with all of its contributing structures. Part III will be the regular construction update, which will be bi-monthly just like all the others.

Quick primer note – Maplewood Park was the name of the old complex. The new one is just called “Maplewood”. With the shorthand for Maplewood Park being Maplewood, it can get confusing.

Let’s start with the background. Love it or not, Cornell University is one of the major defining organizations of the Ithaca area. It employs nearly 10,000 people and brings billions of dollars in investment into the Southern Tier, Tompkins County and Ithaca. That investment includes the students upon which the university was founded to educate.

Traditionally, neither founder Ezra Cornell nor first university president Andrew Dickson White were fans of institutional housing. Their preference was towards boarding houses in the city, or autonomous student housing (clubs, Greek Letter Orgs, etc), where it was felt students would learn to be more independent. This mentality has often underlain Cornell’s approach to housing – it’s not a part of their primary mission, so they only build campus housing if they feel it helps them meet academic and institutional goals. If many potential students are opting for other schools because of housing concerns, or the university is under financial strain because it has to subsidize high housing costs in their scholarships, then Cornell is motivated to build housing in an effort to improve its situation and/or become more competitive with peer institutions.

With that in mind, being one of the top-ranked schools in the world means that, in the historical context of the university’s goals and plans, new housing is rarely a concern. Cornell will update housing in an effort to be more inclusive and to improve student well-being, but with labs, classrooms and faculty offices taking precedence, building new housing is rarely an objective. Only about 46% of undergrads live on campus, and just 350 of over 7,500 graduate and professional students.

From 2002 to present, Cornell has added 2,744 students, with a net increase in Ithaca of about 1900. The net increase in beds on Cornell’s Ithaca campus during that same time period is zero. While Cornell did build new dorms on its West Campus, they replaced the University “Class of” Halls. 1,800 beds were replaced with 1,800 beds. In fact, the amount of undergraduate and graduate housing on campus had actually decreased as units at Maplewood Park and the law school Hughes Hall dorm were taken offline, either due to maintenance issues, or for conversion to office/academic space. When the announcement for further decreases came in Fall 2015, I wrote a rare Ithaca Voice editorial, and even rarer, it brought Cornell out to the proverbial woodshed for poor planning and irresponsibility.

To be fair, while Cornell was the guilty body, removing housing isn’t a problem on its own. It’s when the local housing market can’t grow fast enough to support that, that it becomes a problem. The Tompkins County market is slow to react, for reasons that can be improved (cumbersome approvals process) and some that can’t (Ithaca’s small size and relative isolation poses investment and logistical hurdles). In the early and mid 2000s housing was added at a decent clip, so the impacts were more limited. But housing starts tumbled during and after the recession, and it was unable to keep up. As Cornell continued to add students in substantial quantities, it became a concern, both for students and permanent residents.

By the mid-2010s, Cornell was faced with financial strains, student unhappiness and worsening town-gown relations, all related to the housing issue. As a result, the past couple years have become one of those rare times where housing makes it close to the top of Cornell’s list of priorities.

In weighing its options, one of the long-term plans was to redevelop the 17-acre Maplewood Park property. The property was originally the holdings of an Ellis Hollow tavern keeper and the Pew family before becoming the farmstead of James and Lena (sometimes Lyna) Clabine Mitchell in the early 1800s. In 1802, James was passing through from New Jersey to Canada with plans to move across the border, but stopped in the area, liked it, and bought land from the Pews, then moving the rest of his family up to Ithaca. Apparently there’s a legend of Lena Mitchell attacking and killing a bear with a pitchfork for eating her piglets. Many of the home lots in Belle Sherman were platted in the 1890s from foreclosed Mitchell property.

Like many of the Mitchell lands, it looks like the property was sold off around 1900 – a Sanborn map from 1910 shows a brick-making plant on the property along the railroad (now the East Ithaca Rec Way) and not much else for what was then the city’s hinterland. It’s not clear when Cornell acquired property, but by 1946, Cornell had cleared the land to make way for one of their “Vetsburgs”, also known as Cornell Quarters. The 52 pre-fabricated two-family homes were for veterans with families, who swelled Cornell’s enrollment after World War II thanks to the GI Bill. Once the GIs had come and gone, Cornell Quarters became unfurnished graduate housing, geared towards students with families, and international students.

The Cornell Quarters were meant to be temporary, and so was their replacement. In 1988-89, the university built the modular Maplewood Park Housing, with 390 units/484 beds for graduate and professional students, and an expected lifespan of 25 years. The intent was to replace them with something nicer after several years, but given Cornell’s priorities, and housing typically not among them, it fell to the back burner. As temporary units with marginal construction quality and upkeep, poor-condition units were closed off in later years, and capacity had fallen to about 356 beds when the complex’s closure was announced in May 2015 for the end of the 2015-16 academic year.

Cornell had long harbored plans to redevelop the Maplewood site – a concept schematic was shown in the 2008 university Master Plan. After weighing a renovation versus a rebuild with a few possible partners, the university entered into an agreement with national student housing developer EdR Trust to submit a redevelopment proposal. The partnership was announced in February 2016, along with the first site plan.

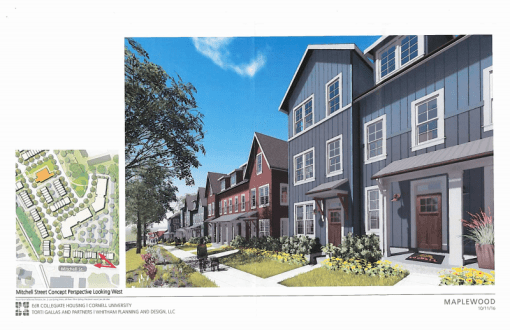

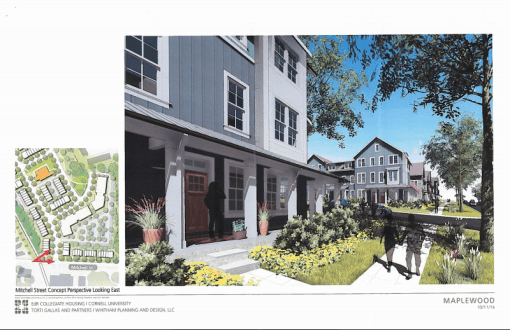

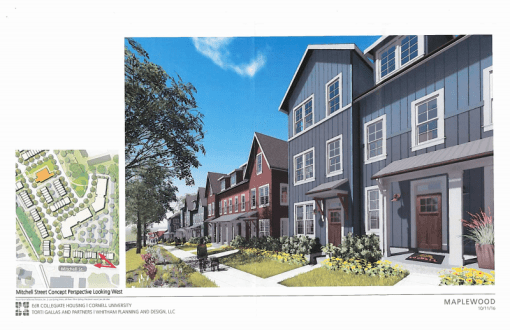

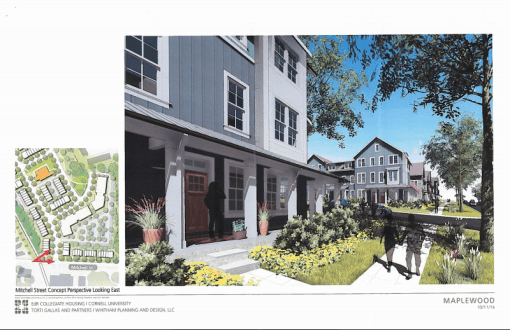

The core components of the project were actually fairly consistent throughout the review process. The project would have 850-975 beds, and it would be a mix of townhouse strings and 3-4 apartment buildings, with a 5,000 SF community center to serve it all. The project adheres to New Urbanist neighborhood planning, which emphasizes walk-ability and bike-ability, with interconnected and narrow streets, and parking behind buildings rather than in front of them. Energy-efficient LEED Certification was in the plans from the start.

However, the overall site plan did evolve a fair amount, mostly in response to neighbor concerns raised through the review process. Many residents on or near Mitchell Road were uncomfortable with multi-story buildings near them, so these were pulled further back into the complex, and late in the process the remaining Mitchell Street multi-story buildings were replaced with very-traditional looking townhomes with a smaller scale and footprint. More traditional designs were also rolled out for the pair of townhouse strings closest to Worth Street, since neighbors noted they would be highly visible and wanted them to fit in. The building planned in the city’s side was also pulled inward into the parcel early on due to neighbor concerns – it became an open plaza and bus stop. The university was fairly responsive to most concerns, although the most adamant opposition didn’t want any multi-story units at all, and really preferred as few students and as few families as possible.

For the record, that is every site plan I have on file. Go clockwise from top left for the chronology. So from beginning to end, there were at least five versions made public. The final product settled on 442 units with 872 bedrooms, with units ranging from studios to 4-bedrooms.

It’s also worth pointing out that the town of Ithaca, in which the majority of the property lies (the city deferred the major decision-making to the town), had a lot of leverage in the details. The town’s decades-old zoning code isn’t friendly to New Urbanism, so the property had to be declared a Planned Development Zone, a form of developer DIY zoning that the town would have to review and sign off on. Eventually, the town hopes to catch up and have form-based code that’s more amenable to New Urbanism. The town also asked for an Environmental Impact Statement, a very long but encompassing document that one could describe as a super-SEQR, reviewing all impacts and all mitigation measures in great detail. The several hundred pages of EIS docs are on the town website here, but a more modest summary is here. If you want the hundreds of pages of emailed comments and the responses from the project team, there are links in the article here.

Some details were easier to hammer out than others. The trade unions were insistent on union labor, which Cornell is pretty good about, having a select group of contractors it works with to ensure a union-backed construction workforce. Also, at the insistence of environmental groups, and as heat pumps have become more efficient and cost-effective, the project was switched from natural gas heat to electric heat pumps, with 100% of the electricity to come from renewables (mostly off-site solar arrays).

Taxes were a bit more delicate, but ended up being a boon when it was decided to pay full value on the $80 million project. It was a borderline case of tax-exemption because Cornell would own the land and EdR would own the structures, and lease the land for 50 years; but Maplewood Park was exempt, so it could have been a real debate. Instead, EdR said okay to 100% taxation, which means $2.4 million generated in property taxes on a parcel that previously paid none. Some folks were also concerned if the schools could handle the young child influx, but since Maplewood Park only sent about 4 kids to the elementary school on average, and the new plan would send 10 students when the school has capacity for another 26, so that was deemed adequate.

On the tougher end, traffic is a perennial concern, and Cornell wasn’t about to tell graduate and professional students and their families to go without a car. Streetscape mitigations include raised crosswalks, curbing, and landscaping, EdR is giving the town $30,000 for traffic calming measures (speed humps and signage) to keep the influx of residents orderly and low-speed. A new 600,000 gallon water tank also has to be built (planned for Hungerford Hill Road).

One of the thorniest issues were the accusations of segmentation, meaning that Cornell was falsely breaking their development plans up into smaller chunks and hiding their future plans to make the impacts seem smaller. This has come in the context of the Ithaca East Apartments next door, and the East Hill Village Cornell is considering at East Hill Plaza. However, neither were concrete plans at the time, and still aren’t – to my understanding, Cornell had some informal discussions about Ithaca East but decided against it early on in the process. And they only just selected a development team for EHV.

In the end, many of the concerned neighbors and interest groups were satisfied with the changes, and actually lauded Cornell and EdR for being responsive. The EIS was formally requested in May 2016. The Draft EIS was accepted in August 2016, public meetings on it were held in October, and the Final EIS was submitted at the end of October. After some more back-and-forth on the details (stormwater management plan, or SWPPP), the Final EIS was approved right before Christmas and the project was approved in February 2017, starting work shortly thereafter for an intended August 2018 completion. With the wet summer, the project managers asked for a two-hour daily extension on construction (8 am-6 pm became 7 am -7 pm) to meet the hard deadline, which the town okayed with a noise stipulation of less than 85 decibels.

Rents for the project, which include utilities, wireless and pre-furnished units, are looking to range from $790-$1147 per bed per month, depending on the specific unit. Back of the envelope calculations suggest affordability at 30% rent and 10% utilities, for 40% of income. Cornell stipends currently range from $25,152-$28,998, which translates to $838-$967/month.

On the project team apart from Cornell and Memphis-based EdR are Torti Gallas and Partners of Maryland, New Urbanist specialists who did the overall site plan and architecture. Local firms T.G. Miller P.C. is contributing to the project as structural engineer, and Whitham Planning and Design is the site plan designer, landscape planner and boots-on-the-ground project coordinator for municipal review. Brous Consulting did the public relations work, and SRF & Associates did the traffic study. Although not mentioned as often, STREAM Collaborative did the landscape architecture for the project. The general contractor is LeChase Construction of Rochester.

So that’s part one. Part two will look at the structures and site plan itself. And then with part three, we’ll have the site photos.