1. So here’s an intriguing update to the stalled redevelopment at 413-415 West Seneca Street. Ithaca Neighborhood Housing Services was preparing to buy the former Ithaca Glass property and its development plans, which had hit a major snag due to structural issues with the existing building, and continued financial issues with pursuing of a completely new build (bottom). INHS was planning on purchasing the site and going with the original plan, which would have added four units to the existing two apartments and vacant commercial space. But someone outbid them for the site. The buyer, who has not finalized the purchase, may elect to use either of the plans designed by STREAM Collaborative, or pursue a different project at the site.

While that plan may have fallen through, it looks like the INHS Scattered Site 2 rehab/redevelopment plan will be moving forward following approval of amendments to the funding plan by the IURA and Common Council. The revised plan will dedicate funds toward the replacement of fourteen units (four vacant due to structural issues) in three buildings to be replaced with a new thirteen-unit apartment building at 203-208 Elm Street on West Hill, and major rehabiliation of four other structures (sixteen units) in Southside and the State Street Corridor.

2. Speaking of sales, here’s something to keep an eye on – the Lower family, longtime Collegetown landlords, sold a pair of prime parcels on October 4th. 216-224 Dryden Road was sold for $2.8 million, and 301 Bryant Avenue was sold for $1.4 million. Both properties were sold to LLCs whose registration address was a P.O. Box. A couple of local development firms like to use P.O. Boxes, but with nothing concrete, it’s uncertain who’s behind the purchases.

301 Bryant Avenue has some historic significance as the formal home of the Cornell Cosmopolitan Club. Founded in 1904 as a men’s organization to provide camaraderie and support for international students attending the university, the 13,204 SF, 35-bedroom structure was built in 1911 and served as the equivalent of a fraternity’s chapter house, providing a shared roof, shared meals, social events, lectures by students and faculty about other lands and cultures, and professional networking for students arriving from abroad. A women’s club was organized in 1921. As Cornell grew and different international groups founded their own organizations, the club’s purpose was superseded, and shut down in 1958. The building was purchased by the parishioners of St Catherine’s a parish center before the new one was built in the 1960s, and served as a dorm for the Cascadilla School before Bill Lower bought the building in 1973. Lower converted the structure into a six-unit apartment building, with the largest nit being eight bedrooms. With an estimated property assessment of $1.27 million, the sale appears to be for fair value – no issues, and no indications of redevelopment.

216-224 Dryden Road is much more interesting from a development perspective. 11,600 SF in three buildings (county data suggests either 14 units, or 9 units and 20 single occupancy rooms), the earliest buildings in the assemblage date from the early 1900s, but with heavy modifications and additions to accommodate student renter growth. Bill Lower bought the property way back in 1968. The properties are only assessed at $1.87 million, well below the sale price. That suggests that a buyer may be looking at redevelopment of the site. The site is in highly desirable inner Collegetown, and the zoning is certainly amenable; CR-4 zoning allows 50% lot coverage and four floors with no parking required. CR-4 offers a lot of flexibility – 119-125 College Avenue and the Lux are recent CR-4 projects.

3. The other recent set of big purchases also occurred on October 4th. “325 WEST SENECA ASSOCIATES LLC” bought 111 North Plain Street, 325 West Seneca Street, 325.5 West Seneca St (rear building of 325) and 329-31 West Seneca Street for $1.375 million. 325 West Seneca is a three-unit apartment house assessed at $200k, 325.5 West Seneca is a modest bungalow carriage house assessed at $100k, 329-331 West Seneca is a two-family home assessed at $360k, and 111 North Plain Street in a neight-unit apartment building assessed at $475k. Added up, one gets $1.135 million, which suggests the purchase price was reasonable.

Given that 327 West Seneca is currently the subject of a moderate-income redevelopment proposal from Visum, one would expect Visum to likely be behind these purchases, right? But the LLC traces back to the headquarters of a rival real estate development firm, Travis Hyde Properties. The whole thing strikes me as a little odd, but who knows, maybe Frost Travis bought the properties as stable assets rather than development sites.

4. Let’s stick with Travis Hyde Properties for a moment – here are the submissions related to his Falls Park Apartments proposal. Readers might recall this is the plan for 74 high-end senior apartments on the former Ithaca Gun site. Drawings here, 138-page submission package courtesy of TWMLA’s Kim Michaels here. Trowbridge Wolf Michaels Landscape Architecture will handle the landscape design, and newcomers WDG Architecture of Washington D.C. are designing the building.

No cost estimate has been released for the project, but buildout is expected to take 20 months. 150 construction jobs will be created during buildout, and the finished building will create four permanent jobs. The project will utilize New York State Brownfield Cleanup Program (NYS BCP) tax credits. In the case of this project, the credits would be a smaller credit to help cover the costs of site remediation insurance, and a larger credit awarded by the state that would cover 10-20% of the project’s property value, depending on whether it meets certain thresholds. It is still not clear at this point if a CIITAP tax abatement will be pursued.

The 74 units break down as follows: 33 two-bedroom units (1245 SF), 9 one-bedroom units with dens (1090 SF), and 32 one-bedroom units (908 SF). All units include full-size kitchens, wood and/or natural stone finishes, and about half will have balconies. Also included in the 133,000 SF building is 7,440 of amenity space, and there will be 85 parking spaces, 20 surface and 65 in the ground-level garage.

A number of green features are included in the project, such as LED lighting, low-water plumbing fixtures, and a sophisticated Daikin AURORA VRV high-efficency HVAC system, which uses air-source heat pumps. It look like there is some natural gas involved, however, for heating the rooftop ventilation units, and in the amenity space’s fireplace.

Due to soil contamination issues, the plan is essentially to dig up the soil and cart it off to the landfill in Seneca County. The soil runs up to 11.5 feet deep, and the building foundation will be 15 feet below current surface level (about 85% of the foundation will be a shallow slab, with deeper piles near the northeast corner). As a result, some of the bedrock will be removed and disposed of as well. What soil does remain on-site will be sealed in a NYSDEC-approved cap. Concerns about VOCs in the groundwater are somewhat mitigated by the geology of the site (horizontal fractures carry the VOCs downhill), but the ground level is a ventilated garage in part to prevent sustained exposure to vapor intrusion. The project will be presented at this month’s Planning Board meeting, where the board is expected to declare itself lead agency for environmental and site plan review of the proposal.

Early sketch plan includes a medical office, retail, market rate housing, and affordable housing. Details about the site and massing of the buildings are still to be determined pic.twitter.com/dU2umdQBpk

— Ducson Nguyen (@duc2ndward) October 10, 2018

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

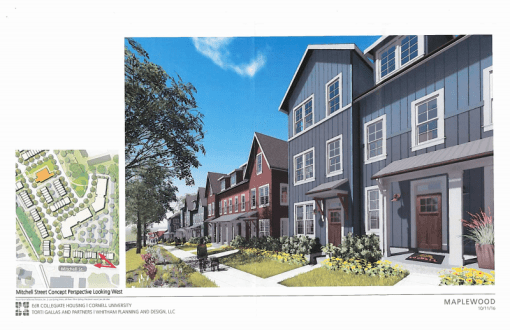

5. So, one of the reasons why the Voice writeup on the Carpenter Park site didn’t include building renders was because in a follow-up phone call for hashing out the emailing of PDF images, Scott Whitham of Whitham Planning was adamant they not be used, describing them as highly conceptual. He didn’t even want to pass them along out of fear they’d mislead the general public. For the merely curious, here are images taken by Second Ward Councilman Ducson Nguyen.

The architecture firm that’s involved with the project is a newcomer to the Ithaca area – Barton Partners, which has a lot of rather high-end, traditional-looking design work scattered throughout the Northeast, as well as a new more modern designs similar to the placeholders. Can’t make any hard conclusions at this point, but a look through their portfolio gives an idea of what one might expect to see with the Carpenter Park redevelopment.

6. The former Wharton movie studio at Stewart Park is slated to become a gallery and visitor’s center, thanks to a $450,000 state grant. The building, which was the studio’s main office from 1914 to 1920, and is currently used by the city Board of Public Works, will be renovated into the Wharton Museum, with exhibit space, a public meeting room, and a terrace / seating area overlooking the lake. The project will be a joint effort by the Wharton Studio Museum and Friends of Stewart Park, with assistance from the City of Ithaca. Todd Zwigard Architects of Skaneateles (Skinny-atlas) will be in charge of designing the new museum space. It will be fairly modest in size, about 1,000 square feet, with the rest remaining for BPW use; the public works division will compensate the loss of space with an addition onto its annex nearby.

The project should dovetail nicely with a couple of other local nonprofit projects underway – the revitalization and expansion of the Stewart Park playground will give younger visitors something to do while their parents or grandparents check out the museum, and there’s potential to work with The Tompkins Center for History and Culture on joint projects that encourage visitors to pay a visit to both Downtown and the lakefront.

7. The Old Library redevelopment is once again the subject of controversy. Due to structural issues with the roof and concerns about it collapsing onto workers during asbestos abatement, the city condemned the building, which changed Travis Hyde Properties plans from sealing the building in a bubble and removing the asbestos before demolition, to tearing it down without removing asbestos from the interior first. Much of the asbestos from its late 1960s construction was removed as part of renovations in 1984, with more in the 1990s, but in areas that weren’t easily accessible, it was left in place.

The new removal plan has led to significant pushback, led by local environmental activist Walter Hang. A petition floating around demands that the city un-condemn the building and then forces Travis Hyde to renovate the building enough to stabilize the roof to remove the asbestos.

While the concern about the asbestos is merited, there are a couple of problems with this plan. It boils down to the fact that New York State code, rather than the city, defines what a developer can and can’t do with asbestos abatement. The two options here are stabilization and removal before demolition of the above-ground structure, or tearing it down piece by piece and using procedures like misting to keep the asbestos from getting airborne, with monitors in place to ensure no fibers are entering the air. The city can’t force a developer to choose one approach over another, if a building is condemned, and the city can’t force Travis Hyde to renovate the building to a state where it wouldn’t be condemned. That would be the NYS Department of Labor’s role. But if the city rescinded its condemnation, a roof renovation would involve removing the existing roof – a procedure that involves misting the on-site asbestos to keep it from getting airborne. With workers going in an out of the building to stabilize the structure and being put at risk by the unstable roof as well as the asbestos, the Department of Labor isn’t going to sign off on anything putting crewmen at risk of a roof collapse.

There is some consternation with this, and that’s fair. The development project did take several months longer to move forward than first anticipated, though had it started on time it’s not clear if the city and THP wouldn’t have been in this position anyway if work had started sooner. Demolition is expected to start within thirty days of the permit being issued (and it has, so in effect, any day now), and take six to eight weeks to complete.

8. Unfortunately, I had to miss this year’s architects’ gallery night, which is a shame because the local firms like to sneak in yet-unannounced plans. Case in point, this photo from Whitham Planning and Design’s facebook page clearly shows something is planned at the site of the Grayhaven Motel at 657 Elmira Road. The Grayhaven has four on-site structures, and the two westernmost buildings look as they do now…but the footprints of the two eastern buildings, where one first pulls in, do not match their current configuration. Intriguing, but also frustrating. The boards on the floor are related to the Visum Green Street proposal, and the other wall board is a North Campus proposal that didn’t make the cut, previously discussed on the blog here.

9. Out in the towns, there’s not a whole lot being reviewed as of late. The town of Lansing will have a look next week at marina renovations, a one lot subdivision, and a 4,250 SF (50’x85′) expansion of a manufacturer, MPL Inc., a circuit board assembler at 41 Dutch Mill Road. The expansion of their 14,250 SF building will create five jobs or less, per site plan review documents.

In Dryden town, the town board continued to review the proposed veterinary office in the former Phoneix Books barn at 1610 Dryden Road, and they’ll had a look at a cell phone tower planned near TC3. Danby’s Planning Board looked at an accessory dwelling application and a two-lot subdivision last week. Ulysses had a look at a proposal for a 6,400 SF pre-school and nursery building planned for 1966 Trumansburg Road, a bit north of Jacksonville hamlet.

The village of Cayuga Heights Planning Board has a single-family home proposal to look at 1012 Triphammer Road, and in the village of Lansing, the Planning Board and Board of Trustees will review and weigh consideration of a PDA that would allow the Beer family’s proposal for multiple pocket neighborhoods of senior cottages to move forward on 40 acres between Millcroft Way and Craft Road. Trumansburg is still looking at the 46 South Street proposal from INHS and Claudia Brenner.

10. Last but not least, the city of Ithaca Planning Board’s agenda for next week. Apart from the long-brewing Carpenter project, there’s nothing else that’s new, continuing the relative lull in new projects. Cornell’s North Campus Expansion continues its public hearing, and the new warehouse and HQ for Emmy’s Organics looks ready to obtain final site plan approval.

1 Agenda Review 6:00

2 Privilege of the Floor 6:05

3 Approval of Minutes: September 25, 2018 6:15

4 Subdivision Review

A. Project: Minor Subdivision 6:20

Location: 111 Clinton St Tax Parcel # 80.-11-11

Applicant: Lynn Truame for Ithaca Neighborhood Housing Services

Actions: Consideration of Preliminary & Final Subdivision Approval

Project Description: The applicant is proposing to subdivide the 1.71 acre property onto two parcels: Parcel A measuring 1.6 acres (69,848 SF) with 299 feet of frontage on S Geneva St and 173 feet on W Clinton St and containing two existing buildings, parking and other site features; and Parcel B measuring .1 acres (4,480 SF) with and 75 feet of frontage on W Clinton St and containing one multi-family building. The property is in the P-1 Zoning District which has the following minimum requirements: 3,000 SF lot size, 30 feet of street frontage, 25-foor front yard, and 10-foot side yards. The project requires an area variance of the existing deficient front yard on the proposed Parcel B. The project is in the Henry St John Historic District. This is an Unlisted Action under the City of Ithaca Environmental Quality Review Ordinance (“CEQRO”) and the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”), and is subject to environmental review.

The story behind this is that for legal purposes, INHS needs to split an existing house from its multi-building lot before it can proceed with renovating it as part of the Scatter Site Housing renovation project. No new construction is planned.

B. Project: Major Subdivision (4 Lots) 6:30

Location: Cherry Street, Tax Parcel # 100.-2-21

Applicant: Nels Bohn for the Ithaca Urban Renewal Agency (IURA)

Actions: Consideration of Preliminary Subdivision Approval

Project Description: The IURA is proposing to subdivide the 6-acre parcel into four lots. Lot 1 will measure 1.012 acres, Lot 2 will measure 1.023 acres, Lot 3 will measure 2.601 acres, and Lot 4 will measure .619 acres. Lot 3 will be sold to Emmy’s Organics (see below), Lot 4 will be left undeveloped for future trail use, and Lots 1 & 2 will be marketed and sold for future development. This subdivision is part of a larger development project that is a Type I Action under the City of Ithaca Environmental Quality Review Ordinance (“CEQRO”) §176-4 B(1) (c) and (j) and B(4) the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”) §617-4 (b) (11), for which the Planning Board made a Negative Declaration of Environmental Significance on September 25, 2018.

The Emmy’s Organics project is really two components – one, the new building in the city-owned Cherry Industrial Park, and two, the city’s (IURA’s) construction of a street extension that would service Emmy’s and two smaller lots which could then be sold to a buyer committed to economic growth for presently low and moderate-income households.

5 Site Plan Review

A. Project: Construction of a Public Road 6:45

Location: Cherry Street, Tax Parcel # 100.-2-21

Applicant: Nels Bohn for the Ithaca Urban Renewal Agency (IURA)

Actions: Consideration of Preliminary & Final Approval

Project Description: The IURA is proposing to extend Cherry Street by 400 feet. The road will be built to City standards with a 65-foot ROW, 5-foot sidewalks and tree lawn, and will be turned over to the City upon completion. The road extension is part of a larger development project that is a Type I Action under the City of Ithaca Environmental Quality Review Ordinance (“CEQRO”) §176-4 B(1) (c) and (j) and B(4) the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”) §617-4 (b) (11), for which the Planning Board made a Negative Declaration of Environmental Significance on September 25, 2018.

B. Project: Construction of a 14-24,000 SF Production Facility (Emmy’s Organics) 7:00

Location: Cherry Street, Tax Parcel # 100.-2-21

Applicant: Ian Gaffney for Emmy’s Organics

Actions: Consideration of Preliminary &Final Approval

Project Description: Emmy’s Organics is proposing to construct a production facility of up to 24,000 SF, with a loading dock, parking for 22 cars, landscaping, lighting, and signage. The project will be in two phases: Phase one, which will include a 14,000 SF building and all site improvements; and Phase two, (expected in the next 5 years) which will include an addition of between 14,000 and 20,000 SF. As the project site is undeveloped, site development will include the removal of 2 acres of vegetation including 55 trees of various sizes. The facility is part of a larger project that includes subdivision of land a 40-foot road extension by the Ithaca IURA extension that is a Type I Action under the City of Ithaca Environmental Quality Review Ordinance (“CEQRO”) §176-4 B(1) (c) and (j) and B(4) the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”) §617-4 (b) (11), for which the Planning Board made a Negative Declaration of Environmental Significance on September 25, 2018.

C. Project: North Campus Residential Expansion (NCRE) 7:20 Location: Cornell University Campus

Applicant: Trowbridge Wolf Michaels for Cornell University

Actions: Public Hearing (continued)

Project Description: The applicant proposes to construct two residential complexes (one for sophomores and the other for freshmen) on two sites on North Campus. The sophomore site will have four residential buildings with 800 new beds and associated program space totaling 299,900 SF and a 59,700 SF, 1,200-seat, dining facility. The sophomore site is mainly in the City of Ithaca with a small portion in the Village of Cayuga Heights; however, all buildings are in the City. The freshman site will have three new residential buildings (each spanning the City and Town line) with a total of 401,200 SF and 1,200 new beds and associated program space – 223,400 of which is in the City, and 177,800 of which is in the Town. The buildings will be between two and six stories using a modern aesthetic. The project is in three zoning districts: the U-I zoning district in the City in which the proposed five stories and 55 feet are allowed; the Low Density Residential District (LDR) in the Town which allows for the proposed two-story residence halls (with a special permit); and the Multiple Housing District within Cayuga Heights in which no buildings are proposed. This has been determined to be a Type I Action under the City of Ithaca Environmental Quality Review Ordinance (“CEQRO”) §176-4 B.(1)(b), (h) 4, (i) and (n) and the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”) § 617.4 (b)(5)(iii). All NCRE materials are available for download at: http://www.cityofithaca.org/DocumentCenter/Index/811

D. Project: Falls Park Apartments (74 Units) 7:50 (Notes above)

Location: 121-125 Lake Street

Applicant: IFR Development LLC

Actions: Project Overview Presentation, Declaration of Lead Agency

Project Description: The applicant proposes to build a 133,000 GSF, four-story apartment building and associated site improvements on the former Gun Hill Factory site. The 74-unit, age-restricted apartment building will be a mix of one- and two-bedroom units and will include 7,440 SF of amenity space and 85 parking spaces (20 surface spaces and 65 covered spaces under the building). Site improvements include an eight-foot wide public walkway located within the dedicated open space on adjacent City Property (as required per agreements established between the City and the property owner in 2007) and is to be constructed by the project sponsor. The project site is currently in the New York State Brownfield Cleanup Program (BCP). Before site development can occur, the applicant is required to remediate the site based on soil cleanup objectives for restricted residential use. A remedial investigation (RI) was recently completed at the site and was submitted to NYSDEC in August 2018. The project is in the R-3a Zoning District and requires multiple variances. This is a Type I Action under the City of Ithaca Environmental Quality Review Ordinance (“CEQRO”) §176-4 B(1) (h)[2], (k) and (n) and the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”) §617-4 (b) (11).

E. Sketch Plan – Mixed-Use Proposal – Carpenter Business Park 8:10

6 Zoning Appeals 8:30

# 3108, Area Variance, 327 W Seneca Street

# 3109, Area Variance, 210 Park Place (construction of a carport)

# 3110, Area Variance, 121 W Buffalo Street (installing a deck and wheelchair lift)

# 3111, Use Variance, 2 Fountain Place (the proposed B&B in the old Ithaca College President’s Mansion)

# 3112, use Variance, 2 Willets Place

7 Old/New Business 8:40

Special Meeting October 30, 2018: City Sexual Harassment Policy, Special Permits (Some of the BZA’s Special Permits Review duties are set to be transferred to the Planning Board).

8 Reports 9:00

A. Planning Board Chair

B. BPW Liaison

C. Director of Planning & Development

9 Adjournment 9:25